If you’ve ever seen someone stumbling through the street, you may have thought to yourself, “this person’s off their rocker!” The origin of the phrase is unclear, but perhaps I could provide some insight through a different type of “rock”. It’s hard to believe that the survival of every human depends on rocks—the rocks in your inner ear. Without these rocks, it would be really hard to wake up in the morning and brush your teeth for work (which for some, may be a blessing in disguise). If someone crashed into your car, and the rocks in your ear were knocked loose, you would most definitely be dazed and confused. In general, it would be quite uncomfortable attempting to discern the location of your body or your surroundings or really anything at all. These almighty, glorious and life-saving rocks, called otoconia, live in the inner ear of all humans and fortunately, they allow us to understand that our head is in motion.

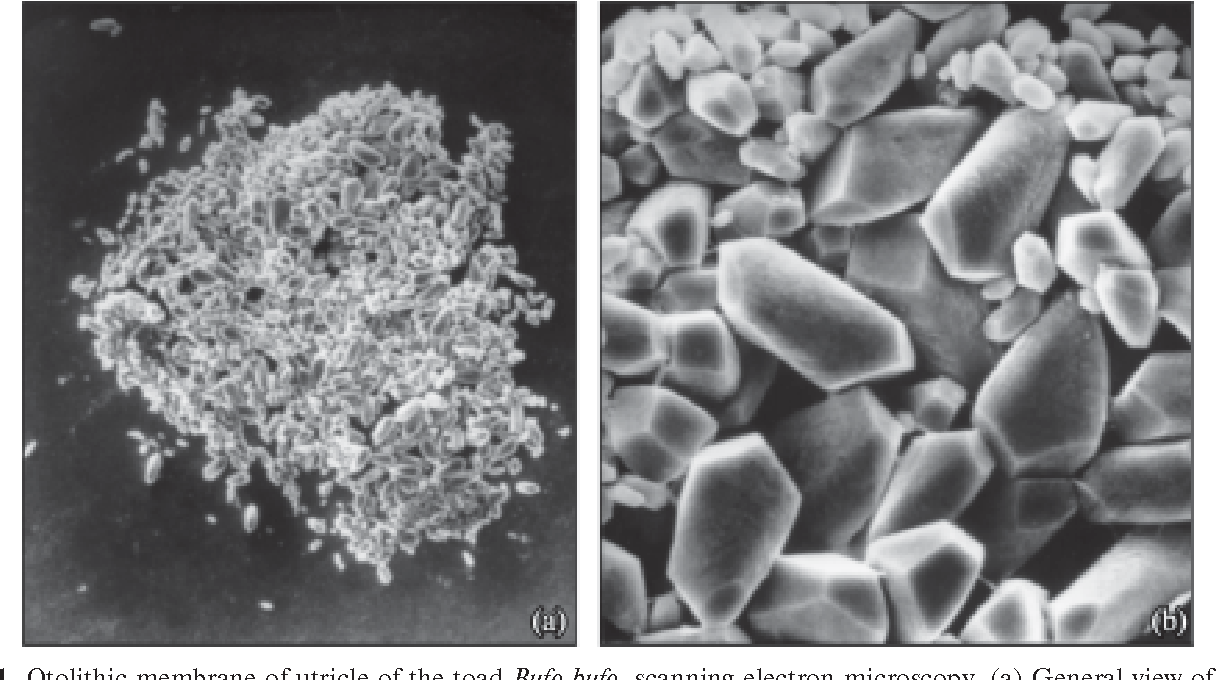

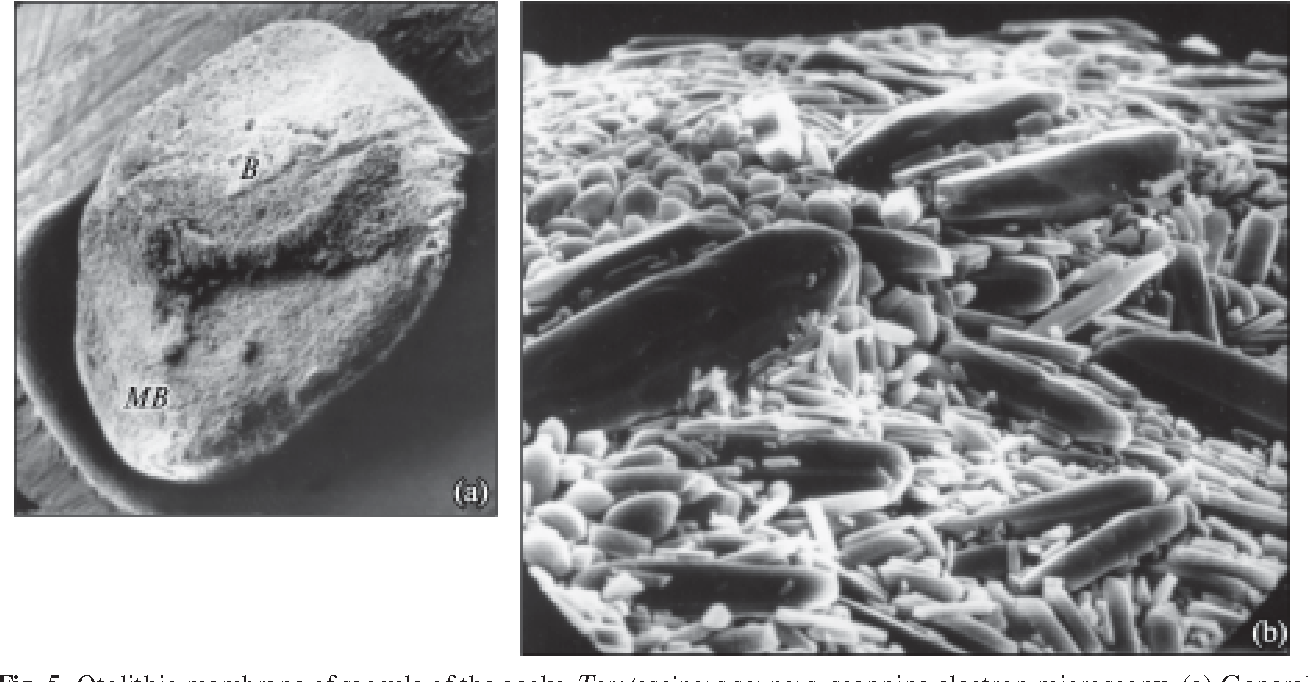

Otoconia look like this:

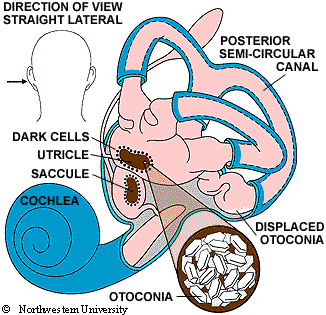

And they’re located here:

Which is located in there:

But way deeper. Closer to your brain.

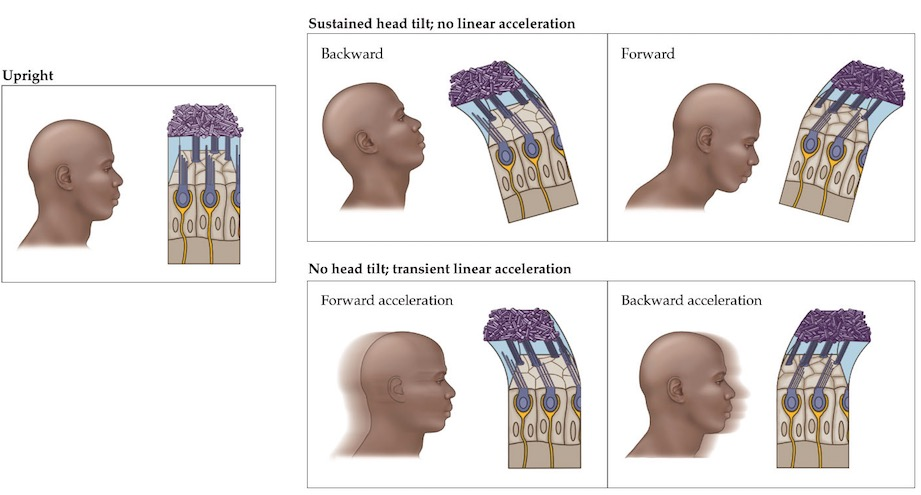

It is no exaggeration that otoconia are actually rocks. Composed of calcium carbonate—the same material found in coral reefs—these “ear stones” rest upon a gelatinous membrane and rub against “hairs” during any tilting motion of the head. The stones closely resemble crystals in their shape and size, and under electron microscopy, appear to be scattered chaotically along the otolithic membrane.

Simply put, the otolithic membrane functions to keep the otoconia in place during tilting motion. Just below the membrane lies a layer of “hair cells”, and when the head tilts or accelerates, the stones shear across the tops of these hair cells, sending a rush of potassium ions into the cell. The slight electrical charge on potassium ions functions as a signal and is relayed to the brain to be encoded as backward/forward tilt (a.k.a pitch) or acceleration/deceleration. Much like an airplane’s flight control system or the halteres of a house fly, the human brain monitors the tilt feedback from the otoconia constantly in order to keep the head upright and maintain balance during movement. On the contrary, while an airplane’s flight control system uses computers and actuators to aid a pilot in proper flight control, the brain uses rocks and “hairs” … To each their own.

It is possible to have a few rocks knocked loose. As a result of either head trauma, advanced age or some other disorder or infection, the otoconia can detach from their membrane and collect along the canals of the inner ear. When this occurs, an individual may have a condition known as Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo, or BPPV, and experience dizziness, nausea, vertigo, lightheadedness and imbalance from loose otoconia. From Oghalai et al., 2000 and Froehling et al, 1991, approximately 50% of all dizziness experienced in those aged 60 and over is due to BPPV. The link here features a nicely-done animation of displaced otoconia, and it’s easy to imagine that this condition would be very uncomfortable.

There are a number of tests that can be administered to make a diagnosis of BBPV and most of them involve a doctor moving the patient’s head around to shake the otoconia back into place. If you watched Looney Tunes or Tom and Jerry back in the day, then some of these methods may bring these sound effects to mind: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EX4i7at27XU

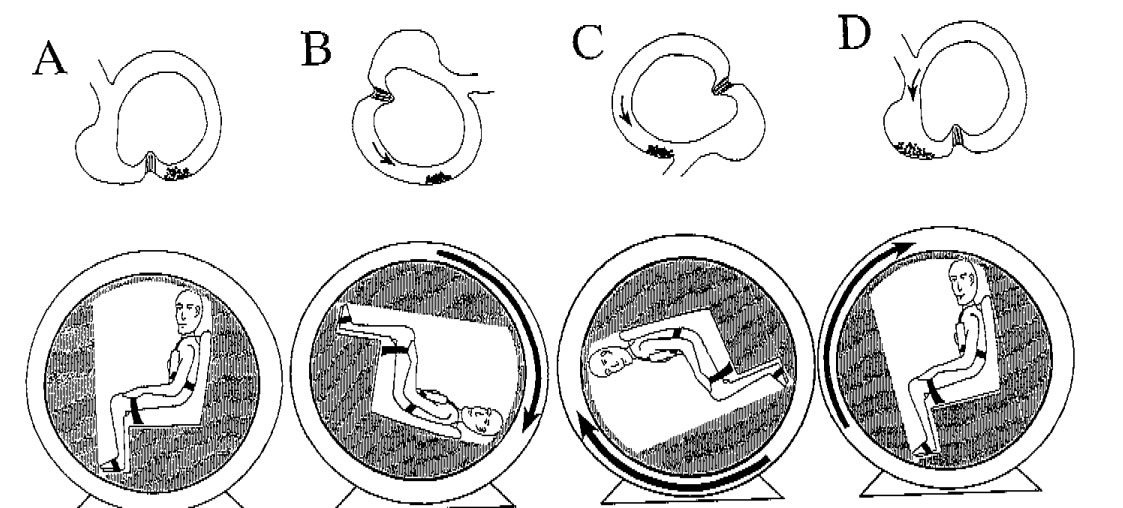

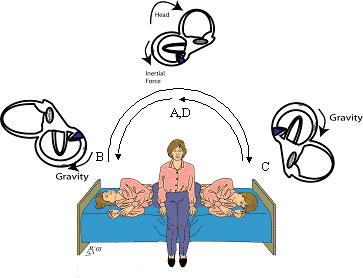

The Semont Maneuver:

According to dizziness-and-balance.com, the Semont Maneuver, named for Dr. Alain Semont, involves a high velocity shaking of the head, as the patient moves from lying on one side of their body to the other, also very quickly.

It should be mentioned that the Semont maneuver is not currently favored in the United States, because these rapid movements are a bit terrifying if you have this condition. However, it is known to be effective.

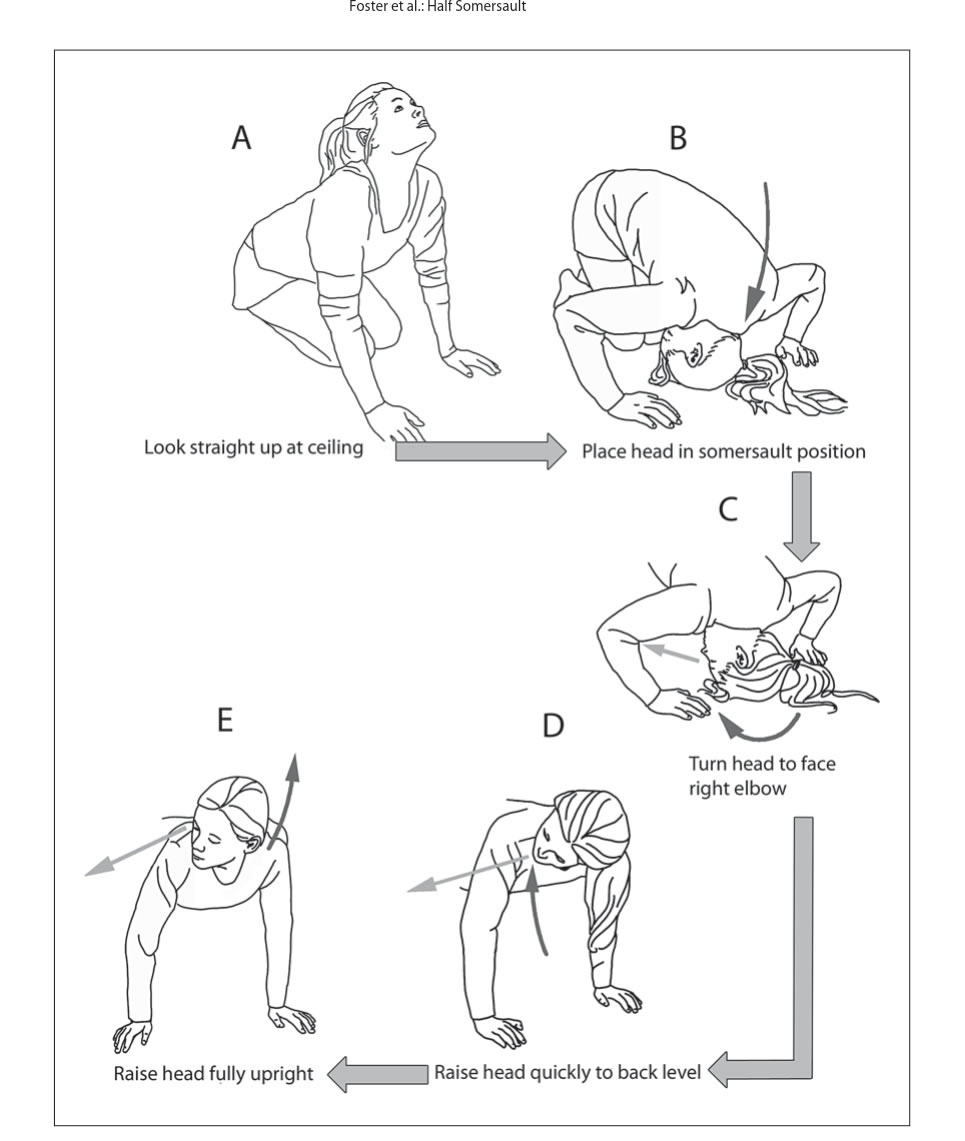

The “Foster” Maneuver

Based off of the Epley Maneuver, the “Foster” Maneuver can be performed at home by patients diagnosed with BPPV and is preferred by many. Diagram:

Lastly, Dr. Timothy C. Hain wrote this section at the bottom of his BPPV home treatment page, which I will copy here:

A Modest Proposal – Another maneuver anyone?

There seems to be considerable willingness in the literature to propose new maneuvers, often named after their inventor, that are simple variants of older maneuvers. Well – there are still a few maneuvers left to adapt (:

If one is willing to engage in athletic positions as in the half-somersault procedure, why not just take things to the logical extreme and do a complete backward somersault in the plane of the affected canal, starting from upright (A below), then to the home-Epley bottom position above (B below), then into the Foster position C – midway between B and C below, and then follow through to position C below (which is also position D of the Foster and home Epley), and then finally to upright again. Stopping for 30 seconds in each position. A full circle. This is a home version of the Lembert 360 rotation described in 1997.

I propose naming it “The full circle maneuver”. Or maybe the full backwards somersault. We do not recommend that people try this maneuver out – as there are some practical issues (i.e. getting from position B to C) and we would not want anyone to hurt themselves. But it should work just as well as the others, as the positions of the head are the same. And that’s the only thing that matters when one considers the efficiency of these maneuvers.