My dad’s dad turned 80 this past June and decided to move out of his house in Lake Zurich, IL and in with my aunt and uncle’s family a few hours south in Peoria. I grew up down the street from my grandparents, and even though my parents moved across town a few years ago and I’ve spent the last few years all over the place, it happened that I was in my hometown in early September when my grandpa moved away; and that meant that it fell to my dad and I to sell or throw away most of his possessions and fix up the house to rent or sell.

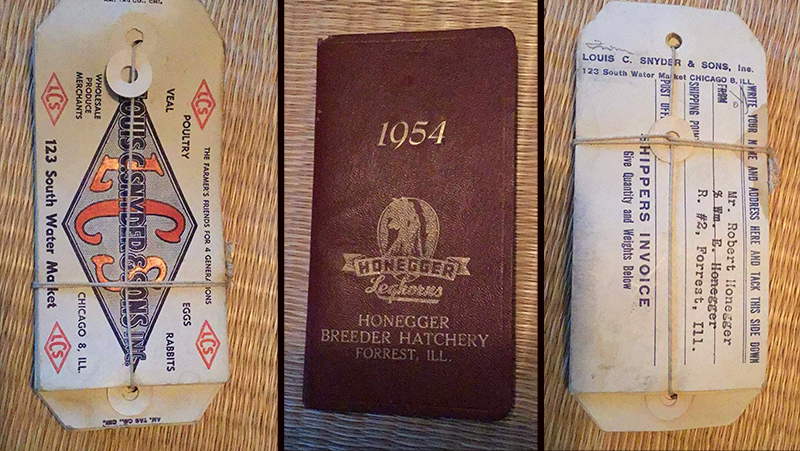

Now, my grandpa, Robert, was born the third of five children in 1938, the coattails of the Great Depression, on a farm in rural Illinois. In those times going into the town a few miles away was a serious ordeal, a trek that nowadays would feel akin to driving from Chicago to Milwaukee at 80 miles an hour. You wouldn’t go into town for just anything—some measly nails, say—and that meant that people kept the most absurd assortment of items lying around just in case they might be useful at some point. My grandpa grew up with that tendency towards austerity, and it has stuck with him for his whole life. This is all to say that he had heaps of what you and I might call junk stored in the garage, basement, and attic; but in sifting through all his stuff in order to decide what to sell, save, or toss, we unearthed a few unexpected treasures, including a stack of receipts from the 1950s from the Chicago Union Stockyards. We decided to keep the receipts—they’re only a shade bigger than a notecard—and the next month I decided to reach out to my grandpa and find out what he knew about the Chicago Stockyards through his and his family’s experiences.

In 1864, nine railroad companies joined forces to buy 320 acres of land just south of the city, forming the Union Stock Yard & Transit Company. There were already several smaller meat markets in the city at the time, but there was widespread clamor from drovers, dealers, and farmers that all expounded the importance of a common center for the whole livestock trade in the city. Chicago — though at the time the population of the city was only 75,000 — was a natural junction for all of the agricultural Midwest that shipped their wares farther east. The land was flat and it was well connected to major waterways through Lake Michigan and the Chicago River.

On Christmas Day in 1865 the Stockyards were opened, and experienced continual growth through the rest of the century. Though the Stockyards were originally used just as a place to route livestock through, by 1870 meatpacking companies had arrived on the scene and the Stockyards became a butchery too. By 1900 the Stockyards alone employed 25,000 people, and 40,000 by 1921. Chicago’s population was over 1.6 million at the turn of the century, not to mention the thousands of railroad workers and farmers who sold their livestock at the markets there, like my grandpa’s family. The Yards had room for around 120,000 live cows, hogs and sheep at any given time; in 1900 it processed 82 percent of the meat consumed in the U.S.

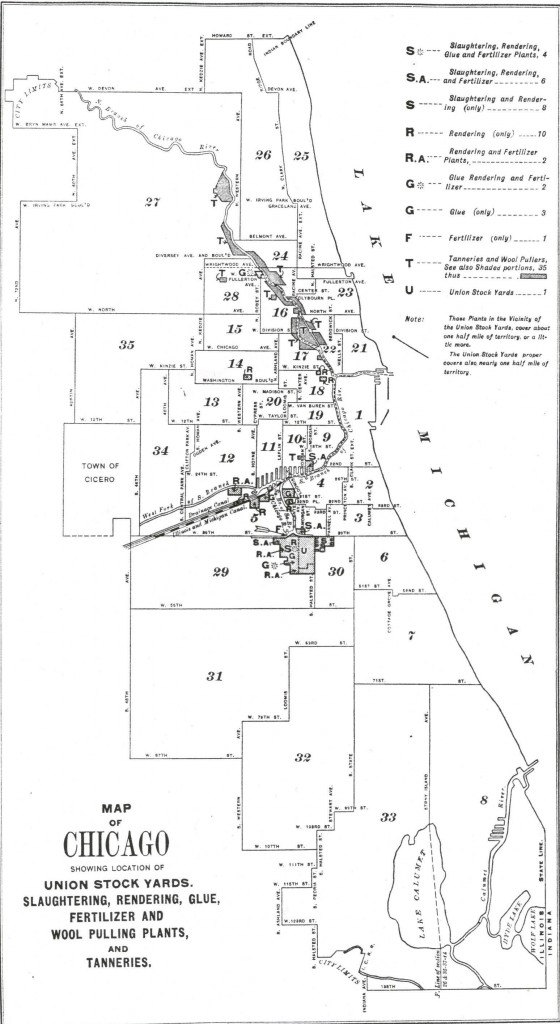

The real success of the Union Stockyards can be most directly attributed to the expansion of the United States’ railroads: to put it in perspective, the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869, just a few short years after the Stockyards opened. By the end of the 1860s refrigerated boxcars were becoming practical too, and these allowed meat to be dressed before being forwarded to retailers, meaning more meat could be shipped at once. And in response to the exploding meat market in Chicago, other businesses opened: wool processors, glue makers, and tanneries, for example.

In 1953 Robert took on the responsibility of managing the hogs from his father. He was a sophomore in high school. They lived outside of a rural town named Forrest, where his family had already rented 80 acres under a landlord/tenant agreement for generations. According to Robert’s memory, the landlord received half the annual harvested crop, and the other half was for the tenant. His dad used a portion of his allotted half for animal feed — for dairy cows and calves, hogs, and chickens — though the arrangement depended on having the grain available, as needed, to sustain feeding the animals. Robert did not personally deliver hogs, but did sell them to an agent who put together several smaller lots and then sold them to one of the meat-packers in Chicago. They were transported by a local Forrest-area trucker who periodically made the run and delivered them to each shipper’s designated agent. Robert was following this method used by his dad, who learned it from his dad before him, and so on back to the 1860s.

By the time Robert was a senior in high school in 1956, he must have seen the writing on the wall, because he decided to attend a small college just over the border into Indiana to study engineering instead of continuing to work the family farm: a mere fifteen years later, the Chicago Stockyards closed. It’s decline was brought about by much the same thing that made all its early success possible: further developments in transportation and distribution, namely the Interstate Highway System whose construction began in 1956. It became cheaper and simpler to slaughter animals near where they were raised, so breeders began selling their livestock directly to local meatpackers who could ship it on refrigerated trucks from their own factories which they built in rural areas, essentially cutting out the Stockyards as an intermediary. But when the Stockyards closed in 1971, Chicago had already gone through its growth spurt, the transformation from an unknown prairie city to the second most populous city in the U.S. (at the time).

In the course of my research I stumbled upon a segment of a short film that a university student made on the last day the Stockyards were open. He interviewed workers, some of whom were old men who had worked there for over fifty years, and whose fathers had worked there during the prior century. Even those grizzled veterans couldn’t help but feel nostalgic about the place. “They’re beautiful memories in the past,” one of them remarked, “but very sad today.” And it’s no wonder: the Stockyards didn’t just shape the lives of the people who worked there, but the city of Chicago too. Nowadays, at least to me, Chicago seems rather disjointed when compared to the U.S.’s other giants: New York, with a history as rich as and older than the United States itself; and Los Angeles in the golden, fruitful West. I grew up in Chicago’s shadow, right on the edge of the suburbs where rural Illinois begins, but could never quite figure out what 10 million people were doing there. But the city’s roots are in the U.S.’s agricultural past — in the Union Stockyards; and how could such a monument do anything but attract people to it? Am I really that surprised, after all, that Robert held on to all those receipts for 65 years?

Sources:

-

https://www.pbs.org/video/chicago-tonight-december-20-2011-chicagos-union-stockyards-40-years/

-

https://www.chipublib.org/blogs/post/technology-that-changed-chicago-union-stockyards-part-one/

-

http://chicagoist.com/2012/08/01/one_for_the_road_75.php#photo-1

-

Knapp, Joseph G. “A Review of Chicago Stock Yards History.” The University Journal of Business, vol. 2, no. 3, 1924, pp. 331–346. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2354664.