In this post, I set out to explain two basic types of microphones and how they work. This post is in some ways a successor to my previous post about signal processing and flow; if you didn’t read that one already, and you have a spare few minutes, I recommend checking that out first. It might provide some useful background information about and motivation for caring about how microphones fit into the whole “getting sound from the air into a computer” business.

Before getting into the specifics of how microphones operate and the technical distinctions between different microphone technologies, let’s start by asking the question: what exactly does a microphone do? If you read my previous post on signal processing (last time I’ll link to that, promise), you’ll recall that microphones are tasked with changing a acoustic signal (air pressure) into an analogous electric signal (measured in voltage fluctuations). This process of converting energy from one form to another is called transduction, meaning that microphones are a type of “transducer.” Our lives are full of transducers. Think of a mercury thermometer that turns the energy of air temperature into some kind of pressure that causes the liquid inside to rise and fall. Microphones do the same thing: they take the air pressure fluctuations created by the strumming of a guitar or the vibration of vocal cords and convert it into electrical energy which can be amplified, recorded, and later re-created.

All microphones are transducers and are designed to accomplish this energy conversion task, but not all microphones do it in the same way. While there have been many different microphone technologies developed throughout the (relatively) short history of audio recording, I’m going to focus on the two most popular types that are used today: dynamic microphones and condenser microphones. Neither microphone type is inherently superior to the other, each has its own set of benefits and malefits which make it a better or worse choice in different recording contexts. I’ll discuss some of these more at the end of this post.

Dynamic Microphones

If I asked you to close your eyes and imagine a microphone, it’s likely that you would have conjured an image of the microphone depicted above, the Shure SM-58 Dynamic Vocal Microphone. The SM-58 was developed in 1966 and has been the world’s best-selling microphone ever since, favored by touring musicians due to its rugged construction, simplicity, and affordability. If you go ahead and Google your favorite band and look at concert photos, there’s a very good chance that the lead singer is holding one of these in their hand. The SM-58 is the prototypical example of a dynamic microphone. But let’s take a look now at what’s going on underneath its iconic spherical steel mesh grille.

This next section is going to include some technical explanations that might seem off-putting to someone who has bad memories of their high school physics class. If you feel your eyes glazing over, just keep in mind what our energy conversion goal is: sound waves to electrical signal. Something inside the microphone has to react to the stream of changes in air pressure and somehow create electrical charge in the process, a process which kind of seems like magic. And what is usually responsible when some technical process seems like magic? That’s right: magnets.

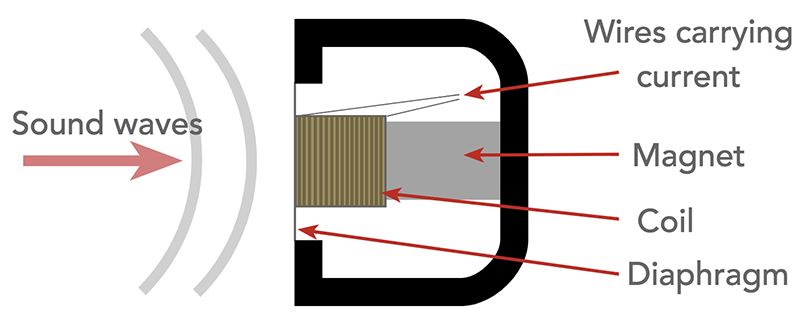

The diagram above depicts the internals of a dynamic microphone. The first part worth noting is the diaphragm. This is usually a very very thin piece of material that moves back and forth when it comes into contact with sound waves—think of the taut membrane stretched over a drum. The diaphragm interacts directly with the stream of sound waves, vibrating upon contact with them and thus converting the form of energy from acoustic to mechanical. But it’s not just the diaphragm which moves. The next part of the diagram, the coil, is attached directly to the diaphragm in dynamic microphones, and therefore moves back and forth as well. This movement in response to the incoming sound saves is where the name ‘dynamic’ comes from: things are actually moving around in there!

Here’s where the magnet comes in. You’ll notice in the diagram that the coil is surrounding a stationary magnet. For reasons a little outside my realm of comprehension, when you move a metal coil inside of a magnetic field, electrical fluctuations are generated in the coil corresponding to the relative movement of the coil and the magnet. You might remember doing an experiment in a physics class which proves this. As the coil moves back and forth along the magnet, an electrical current is generated and sent down the wires attached to it, and violà! We’ve gone from acoustic energy to electrical! Because of this interaction between the coil’s movement and the magnet, the operative principle that allows dynamic microphones to function is electromagnetism.

Condenser Microphones

If you’ve ever used a “shotgun” microphone, the kind that you might place on top of a video camera and point in the direction of the thing you are trying to record, then you have probably used a condenser microphone. The tiny lavalier microphones that you see clipped to peoples’ lapels during interviews? Also mostly condenser microphones. While there is not one single condenser microphone with the popularity of the Shure SM-58 that we looked at in the last section, they are no less widely used in the world of recording. While dynamic microphones rely on the magic of magnets to function as transducers, condenser microphones have a completely different strategy for converting acoustic energy into electrical energy.

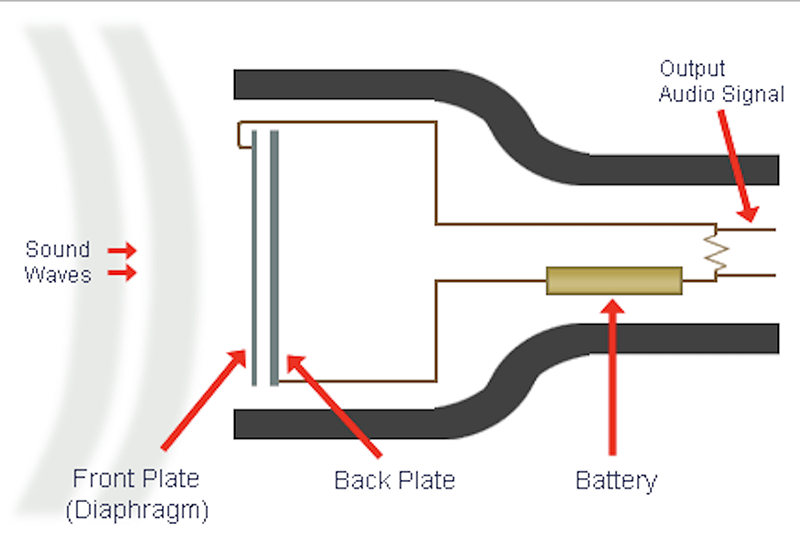

In a condenser microphone, there is no magnet, but there must be a power source. Depending on the microphone, this can either be provided by a battery inside the microphone or it can be sent to the microphone from the device that it is plugged into using a standard called phantom power. Why does there need to be a power source? Let’s take a closer look at the diagram.

Remember learning in high school physics class that electrons will flow from areas of positive charge to areas of negative charge? Well, that’s basically how condenser microphones work. In fact, “condenser” is just an older word for “capacitor”, a concept with which you may be more familiar. A capacitor is an electronic component that can store an electric charge, kind of like a battery, but different in some essential ways. While capacitors were traditionally used in electronics to hold a charge and then discharge it very quickly, like in the flash on your camera, some clever engineers figured out that they could also be used as sensors.

When hooked up to a battery or other power source, the polarized front and back plates in the diagram above create a capacitor whose capacitance is controlled by the distance between the plates. The front plate serves as the diaphragm, free to move as it interacts with incoming sound waves, causing the capacitance to change as the air pressure around it does. A clever circuit design involving a resistor (not pictured in the diagram above) allows this change in capacitance to be measured as a change in electrical potential energy, in volts.

Because the diaphragm in a condenser microphone isn’t attached to a (relatively) heavy metal coil, it is able to respond to much finer changes in pressure than most dynamic microphones, making it more suited to capturing high frequency sounds. The main downside to condenser microphones is the need for an external power supply, although some variations on the condenser microphone, known as the Electret condenser, do not require this.

So which is better?

Despite their technical differences in how they achieve this goal, both dynamic and condenser microphones are transducers, converting acoustic energy to electrical signal. Neither technology is inherently better than the other, but as I mentioned earlier, there are certain use-cases that favor one method of transduction over the other. Dynamic microphones are a favorite among stage musicians, live concert engineers, and people who need to record really loud sounds because of their comparable durability and ability to function without external power. Field reporters, film studios, and nature recorders might prefer condenser microphones because of their very accurate frequency responses.

There is no clear answer to the question of which microphone is the best overall, and even for each situation, it can be muddy, a lot of it comes down to taste, preference, budget, and circumstance. Hopefully you are now inspired to go and experiment with the two types, listening for the differences in sound created by the two different transduction technologies. If you aren’t someone that works with microphones and sound (as you probably aren’t), I hope that from now on, when you are watching the news, at a concert, or listening to music, you think about the engineering marvels at work in bringing that sound from its source to your ears.