Imagine the scene: it’s a crisp fall night, and you’re inside the impossibly European confines of a spacious, Altbau apartment in Linz, Austria. You’ve arrived at the party and the visual dissonance takes a minute to digest – clean, elegant décor is juxtaposed against the streetwear-clad DJs and electronic music enthusiasts who frequent Linz’s most beloved dive bars. You’ve caught the party on an upswing; something on vinyl spins in the background and glasses are filled and refilled with open bottles on the kitchen island. You can’t help but notice that your prissy, velvet shirt doesn’t quite fit with the blur of streetwear in the room — oversized, vintage Adidas, Fred Perry sweatshirts, and sleek, Acne Studios jewelry. Skinny Russian cigarettes dangle between fingers, and new-wave fanny packs, draped across the chest, are most likely stuffed with rolling papers and tobacco.

The current heartbeat of fashion is arguably luxury streetwear. Even tucked away in Austrian obscurity, not only is the aesthetic sustained, but one designer and his brand dominate the discussion: Virgil Abloh, and his ever-controversial label Off-White. I didn’t spot a single Off-White piece in the room, and yet, the brand topping Q3 in Lyst’s 2018 quarterly index was energetically discussed with sour disdain, ambivalence, and plain dislike. To this Austrian sub-crowd, Off-White is overhyped, oversimplified, and overpriced. Equipped with only basic knowledge of the brand (and anticipating Off-White/Virgil recurring as a conversation topic), I was inspired to learn all I could about Off-White: the brand that sells through $1,000 sweatshirts and creates sneakers that resell at 450% above retail (think $800+ Nikes).

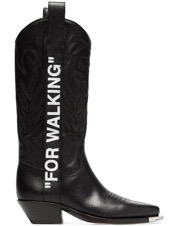

Off-White’s controversy lies mainly in the aesthetic it propagates. Virgil’s Milan-based brand is easily recognizable by its graphic, yet minimalist visual concept. Virgil stamps his Off-White pieces with to-the-point, anodyne words and phrases. Most text is written in Helvetica typeface, almost always in quotation marks: shoelaces with “Shoelaces” printed on them or a scarf with “Scarf” in bold, intarsia letters. A black, leather tote with “Sculpture” in white letters sells for over $1,000, and a pair of leather, cowboy-inspired boots labeled “For Walking” retails for $2,290. All of these items can be found on the Off-White website, aptly labelled “website.”

Sky-high prices, in regard to any brand, almost ask for a scoff or an upturned nose. However, my learning endeavor revealed how misaligned my preconceptions were with the mind behind Off-White. I used to live firmly in the ‘ambivalent’ camp regarding Virgil and Off-White — streetwear wasn’t super relevant to my sartorial choices, and luxury wasn’t (and honestly still isn’t) financially accessible. To Virgil Abloh, “you can use typography and wording to completely change the perception of a thing without changing anything about it. If I take a men’s sweatshirt and write ‘woman’ on its back, that’s art.” To him, the division between art and fashion doesn’t really have to exist. This philosophy drives his designs.

Virgil makes very deliberate design choices. Helvetica was not random, but chosen because it references the mid-century aesthetic exemplified by one of Virgil’s earliest influences at the Illinois Institute of Technology, where he earned his Master of Architecture. Virgil studied the work of German-American architect Mies van der Rohe, who directed the Bauhaus movement just before modernist art was banned by the Nazis. Mies left Germany shortly thereafter, and moved to Chicago to head the architecture department at IIT. Nowadays, Helvetica can be considered a masterpiece of the twentieth century. It is an ubiquitous font that disappears in plain sight – for example, the words you are reading right now are being displayed in Helvetica. Developed in 1957, it is the font “used in the logos of American Apparel, General Motors, Panasonic and BMW, as well as on federal income tax forms and the insides of NASA’s space shuttle.”

Virgil’s trademark quotation marks are both a design refrain and a pointed use of punctuation, meant to invoke a specific mood and mindset. Quotations create instability, as empirical facts are never in quotations. Furthermore, quotations proposition the reader to question the information between the speech marks. Virgil explains this concept in an interview with the Berlin-based magazine O32c, a publication that contextualizes fashion within a wider cultural setting. Journalist Thom Bettridge recalled in the piece: “quotation marks are one of the many tools that Abloh uses to operate in a mode of ironic detachment… Abloh rejects the who-did-it-first mentality of previous generations in favor of the copy-paste logic of the Internet and its inhabitants. His new order is protected by a fortress of irony.” This is how Virgil asks the reader to consider the difference between a handbag and a piece art – is there really a difference?

Virgil’s Off-White designs provide a fresh angle on the complicated relationship between fashion and art, though this conversation isn’t entirely new. Dadaism pioneer Marcel Duchamp famously questioned fundamental assumptions about art with his concept of the Readymade. By taking everyday objects (most notably, a urinal) and presenting them as art, Duchamp asked us to consider: What constitutes art? What can be art? Does art have to be beautiful? In a way, Virgil’s Off-White is a second renaissance of this line of questioning. Virgil’s conceptions of what is good, beautiful, and important once again blur our understanding of art and fashion as separate entities. Furthermore, Virgil seems to define beauty in part by modern metrics such as impact and relevance. In 2018, perceptions of importance and number of hashtag mentions per hour do matter for brands – ask any one of the 5.4 million Instagram followers he has garnered.

Throughout the industry, Virgil Abloh is viewed as extremely media-literate, meticulous, and hard-working. In addition to Off-White, Virgil was recently appointed as the artistic director for Louis Vuitton menswear, and is the first Black man to hold this position in Vuitton’s 164-year history. He is also the first true Midwesterner in the position – he currently lives in Lincoln Park with his wife and two kids, but was born and raised in Rockford, Illinois to Ghanaian parents.

Without any base information on Off-White or Virgil Abloh, a superficial glance at the brand might make Virgil and his designs seem gimmicky. This take would reduce Off-White to what you might have already concluded about fashion as a whole – it is thoughtless and vapid.

Fashion will always be subjective, but Virgil Abloh is objectively a respected fixture in the industry. Regardless of your opinion on Virgil and Off-White, customers and counterparts alike acknowledge his influence and innovation. Moreover, they acknowledge that the “branded sensationalism” he has created cannot be reduced to empty buzz. Virgil aims to provoke from a genuine place of societal reflection, using fashion as a vehicle. Virgil’s Off-White brings multiple fields into a fruitful discussion, and Off-White’s ability to inspire meaningful conversation is probably why Virgil Abloh stands among figures like Justin Trudeau, Meghan Markle, and Oprah on Time’s 2018 100 Most Influential People in the World list.

Sources:

- https://www.complex.com/style/2018/10/off-white-is-now-the-most-popular-fashion-brand-according-to-report

- https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2018/08/virgil-abloh-louis-vuitton-designer-director

- https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/fashion-show-review/branded-sensationalism-at-off-white

- https://www.highsnobiety.com/2017/08/30/virgil-abloh-off-white-quotation-marks/

- https://www.vogue.com/article/virgil-abloh-mens-artistic-director-louis-vuitton-spring-2019-chicago

- https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/dada/marcel-duchamp-and-the-readymade/