This week’s post is written with inspiration from my young and bright cousin, Karston Ryan. A couple of weeks ago I asked him if he would like to write a post on our TWIL page here, and he graciously declined my offer. However, he mentioned that he was curious about something called a gravity model. Luckily, I have no prior knowledge of this topic and it sounds intriguing, so hopefully you readers out there and myself will learn something new together as I write this post. This one’s for you, cuz.

A quick, preliminary Google search of the “gravity model” yields insight into its application in the social sciences. In essence, gravity models predict relationships between people, places, and goods in terms of Newton’s law of gravity: particles attract each other with a force directly related to the product of their masses and indirectly related to the square of the distance between their centers. There are many, many types of gravity models. Isard’s gravity model of trade, Ravenstein’s gravity model of migration, the gravity model of spatial interaction, the Zelinsky model, and so on. Flipping through these, I found one specific application of the gravity model that perhaps most, if not, all of us can relate to: traffic flow.

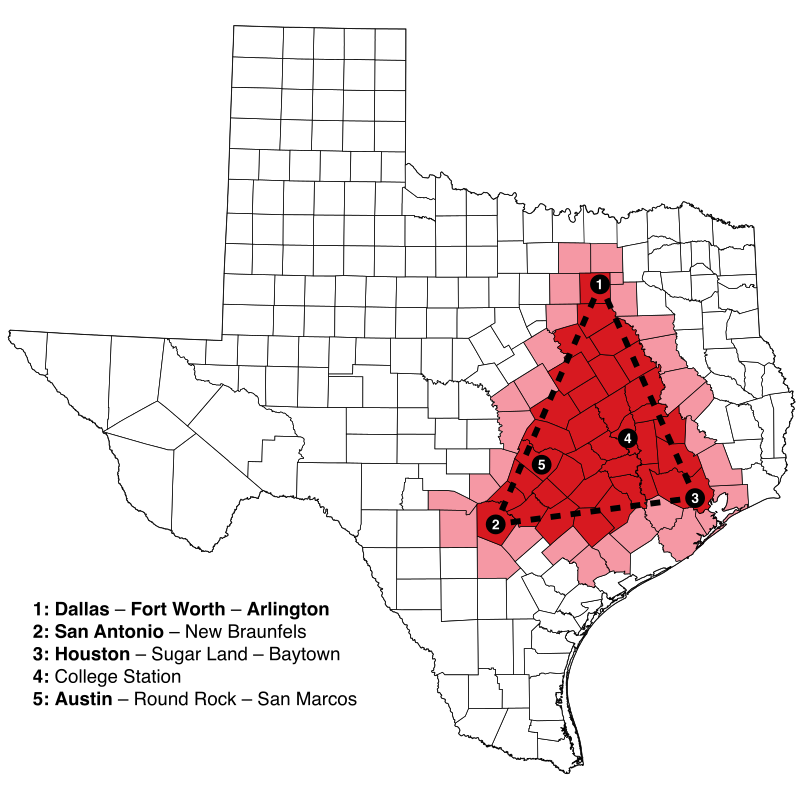

Traffic flow is dependent on the gravity model of migration, where the degree of interaction between two places is dependent on the location of the place and its importance. Much like particles in a Newtonian model, if a city with a large degree of “importance”—i.e. population, or “mass”, commerce, etc …—is located close enough to another city of equal importance, the degree of migration will increase between them. If the locations are farther apart, the degree of migration will decrease. I think a map of the “Texas Triangle” is a good example for applying this model:

Between Dallas and Austin, a 2-4 hour drive depending on traffic, the populations are similar: about 1 million in each city. This drive is typically very smooth and uneventful with the occasional light traffic, depending on the day, time and weather. A gravity model would predict a large degree of migration between the cities over the span of, say, five years and as such the volume of traffic would be substantial. The same can be said of any two or three cities within the triangle, since they are heavily populated and within 5 hours driving of one another. If we narrow our scope to smaller, population-heavy pockets within the Dallas city limits, the nature of traffic flow is more applicable to the gravity model. My home city, Desoto, TX, is located within Dallas county and has a population of 53, 568 (2017). I frequently drive between my home and Richardson, TX with a population of 116,783 (2017). The distance between the cities is 29.5 miles. On average, it takes me about an hour to an hour and a half to arrive in Richardson in the morning on a weekday, and the same amount of time to return home on a weekday in the evening. Of course, we can explain away these travel times as due to rush hour and highway construction and so on, but traffic flow and the gravity model include some other interesting things to consider.

Traffic flow is determined by a three-phase traffic theory (developed by Boris Kerner in ’96) which includes:

- Free flow

- Synchronized flow

- Wide moving jam

My commute includes a minimal amount of “free flow”, which is the relationship between the number of vehicles over time and the vehicle density over distance. If there were very few traveling vehicles alongside of me over my 30 mile drive, then I would have a smooth, stress-free trip to Richardson. Unfortunately, Richardson lies on the other side of Dallas and the highways mix together in the middle to bring all the commuters at once into Dallas.

Skipping the “synchronized flow” for a second, my commute is almost entirely that of a “wide moving jam.” Traffic of this nature moves upstream through bottlenecks upon the highway. This phenomena is known as such because, despite the bottlenecks, the traffic jam will make an attempt to continue through the bottleneck at the same velocity at which it entered, so the jam as one “wide moving” unit “jammed” into a small hole.

“Synchronized flow” can be described as a continuous flow of traffic with no stopping, and this is interesting because it demonstrates a strange tendency for a large number of individuals in different vehicles, moving to different places, to unconsciously act in synchrony due to the nature of their surroundings. During this flow, the vehicle speeds tend to synchronize across multiple lanes of traffic and within each lane of traffic. This explains why you’ve sat in a “wide moving jam”, coasting along together with the lady in the lane over who has been jamming to Beyonce for the last 15 mins, and then suddenly, it seems as if the traffic disappears and everyone resumes their normal travel speeds. Despite the bottleneck having been conquered, the cars on the highway were still moving in synchrony until the farther cars ahead sped forward once again.

In terms of the gravity model, well, a lot of people travel across the highways in Dallas to reach population centers outside of Dallas for work or school. A map of Dallas reveals this nature of the commute, as downtown Dallas is located at the hub of a wheel of interconnected highways.

For those of us that travel to work or school daily, I think the gravity model is an interesting application to commuting and can be applied between locations of shorter distances and smaller populations with as well. You might even think of the gravity model at play between your living room and the kitchen during Thanksgiving. I hope the traffic in the hallway is free and uncongested. 😉