This week, I’d like to share the first in a two-part series, in which I talk through some architectural examples of two concepts—restoration and obsolescence—that have been floating around in some of the media I’ve been consuming recently. I’m going to start with restoration.

(A side-note: part of the reason I’m interested in these two ideas together is because of The Future of Nostalgia, a book I read a little bit of earlier this year. The author writes a little about how nostalgia, at first considered quite a serious disease, was cured in two different, opposite ways. During the 18th century, when Swiss soldiers serving abroad in France were beset by nostalgia, it was a sickness induced by “rustic mothers’ soups, thick village milk and the folk melodies of Alpine valleys[!]” — the only cure was to send them home. (These afflictions were deeply stereotypical, apparently; Scottish soldiers had a similar reaction to the sound of bagpipes.) But when French soldiers suffered from nostalgic sickness during the French Revolution, one doctor wrote that “nostalgia can be defeated by inciting pain or terror. One should tell the nostalgic soldier that ‘a red-hot iron applied to his abdomen’ will cure him immediately.” These are the two remedies for nostalgia, then: a return to the past, or a violence inspired by revolution.)

This week, I’ll focus on Giovanni Piranesi and his famous engravings of ancient Rome. Piranesi was an 18th-century Italian artist who was born and lived most of his life in poverty. Though from Venice, he moved to Rome at age seventeen, persuaded at least in part by a girl he was in love with, who, in the words of one of Piranesi’s biographers, “spoke to him of Rome, of Rome with its infinite Art treasures.” (She later “threw him over,” in the words of the same biographer, and married the Count of Amalfi.) There, he studied architecture and etching. When he was twenty, he tried to murder one of his masters who had refused to teach him the secret of using aqua fortis—nitric acid—to make engravings.

I hope that gives at least some sense of the kind of personality we’re dealing with. (If not, our friend the biographer provides a helpful list of descriptors: “jealous,” “perhaps vain to a high degree,” “perpetually involved in some sort of dispute.”)

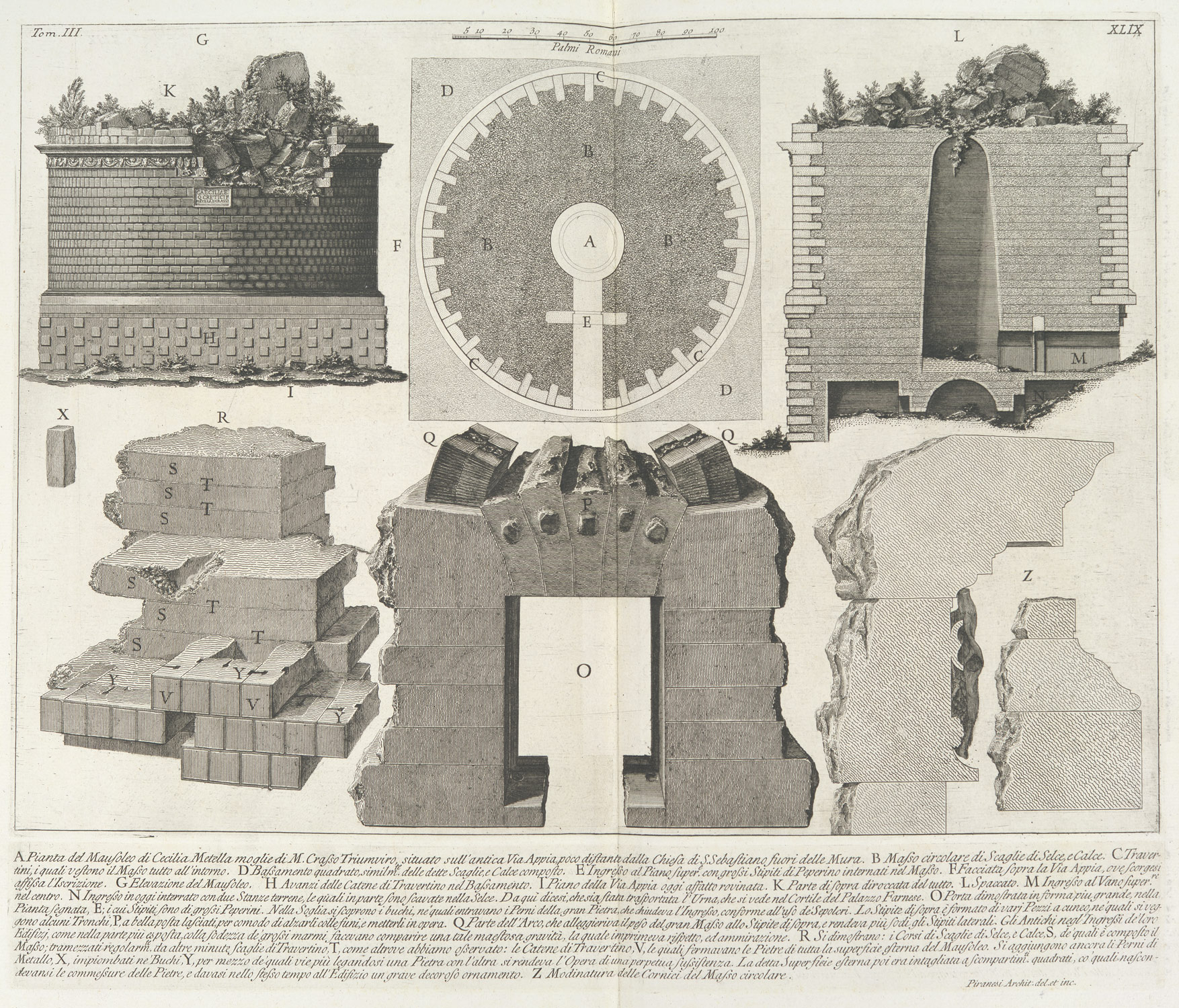

In 1756, Piranesi published Le Antichità Romane, a four-volume book of etchings. The volumes are an artistic, archaeological exploration of Ancient Rome, with detailed renderings of remaining ruins alongside theorizing about what the original might have looked like. Take, for instance, this work, which describes the mausoleum of Caecilia Mettela, daughter-in-law of Marcus Crassus, who formed part of the First Triumvirate alongside Julius Caesar. For all its beauty and complexity, Piranesi’s work is basically a modern look at antiquity (e.g., you can see rubble and foliage in a few of the drawings).

The pictures in the Antichità Romane were mostly attempts to do archaeology, focusing on the ancient structures by themselves; Piranesi would later publish Vedute di Roma, a more artistic work depicting Roman ruins in their modern context. Below is his drawing of the atrium of the portico of Octavia, an old structure restored by Augustus, the first emperor of Rome. Piranesi’s 18th-century drawing places the portico in an 18th-century context: there is (again) the stray plant growth, fish market stalls running along the street outside, women dressed in wide Mantua gowns.

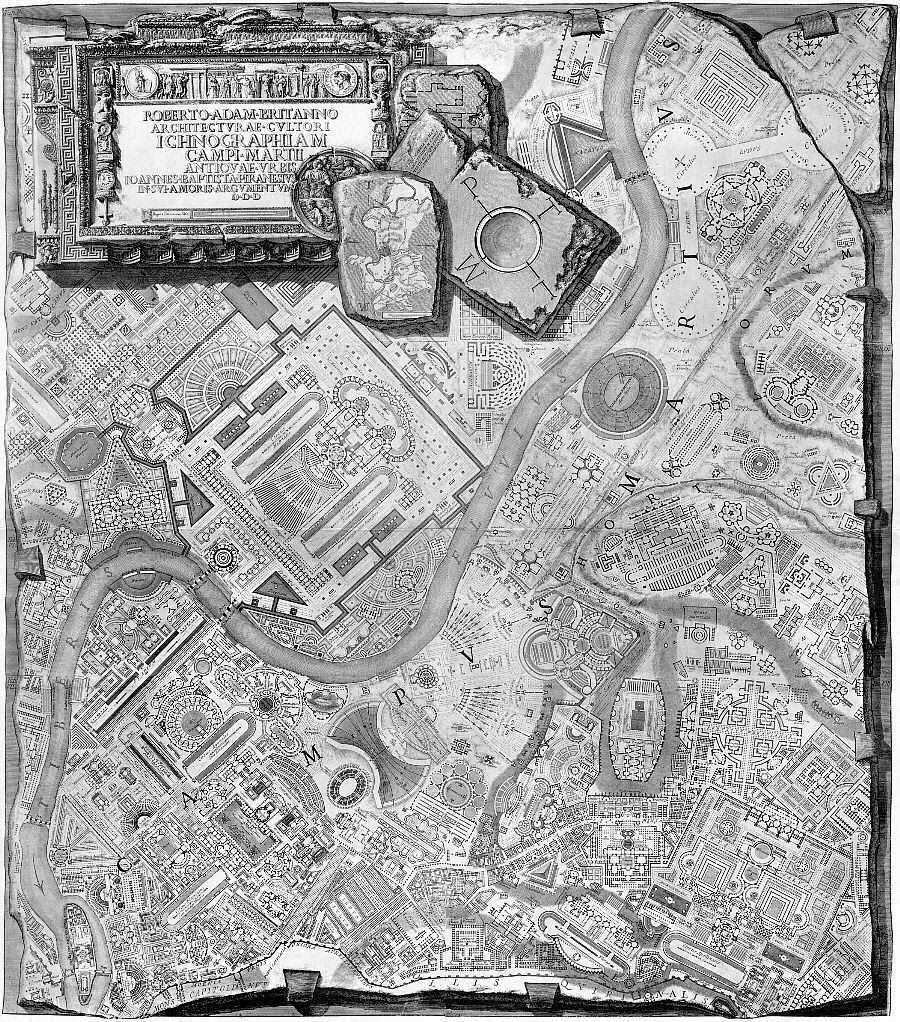

Both of these series, the Antichità and the Vedute, are interesting and beautiful in their own right, but the most fascinating work that Piranesi created, in my opinion, was the Campius Martius antiquade Urbis from 1762. Ostensibly, this volume of etchings sets out to reconstruct the Campo Marzio, a part of Ancient Rome sandwiched between the river Tiber and the walls of the city proper. In reality, it’s a strange mixture of history, fiction, and semi-fiction blended together. Let me begin with a couple of plates from the work.

(Neither of these tiny reproductions do the full-scale versions justice; if you have a chance, go and look at them in detail here and here.) Anyway, these two plates give a good sense of the project. In the top one, “Scenographia Campi Martii”, there’s a horseshoe-shaped track with a hard-to-discern structure in the middle of it. According to architect Stanley Allen, those are the only modern-day remains of the Stadium of Domitian. (“Rome’s first permanent venue for competitive athletics,” says Wikipedia!) But Allen also points out that the suggestion that the stadium, when Piranesi drew it around 1760, just stood by itself on an arid, marshy plain is a lie, intentionally leaving out the churches and houses had been built over its remains during the medieval era.

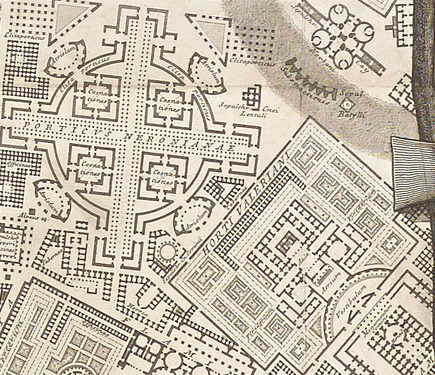

So part of what Piranesi does is remove all the interceding history between himself and the past, and then nevertheless represent the stadium as a historical ruin, something that’s been worn down by time and neglect. He also places the actual and imaginary next to each other. The second plate above is “Ichnographia Campi Martii Antiquae Urbis”; at first glance, it just looks like a blueprint for a city. But if we zoom in a little bit…

(This is from the bottom right corner of the bigger plate, if you’re following along at home.) I want to talk about two structures here. The first is the Horti Valeriani, which is notable for a couple of reasons. It belonged to the family of the husband of Melania the Younger, a notably ascetic saint who gave large chunks of her inherited wealth. (No word on whether she convinced her husband’s family to do anything with the Horti Valeriani.) The second is that it was plundered by the Visigoths the first time they sacked Rome. Anyway, it’s a real, once-extant historical building. Then there’s the Porticus Neronianae immediately to the northwest. That’s a completely fictitious building, which doesn’t and never existed. It’s the same across the map — real buildings mingle with fake ones, as well as real buildings relocated from their original spots, placed somewhere else on the map according to whatever plan Piranesi had in mind.

Finally, if you’d like to explore Piranesi’s work further, I’d recommend Quondam, a bizarre, half-conspiratorial project from architect Stephen Lauf that speculates about the Campo Marzio project in great, frenetically hyperlinked detail. For example, the description of the Porticus Neronianae runs as follows: “the shape of a large cross within a circle (a composition, coincidentally, that follows the circle/square juncture pattern similar to the Timepiece gauge of the theory of chronosomatics.)” I’m not quite sure what this means; a quick Google search for “chronosomatics” turns up more links, some only cached, to Quondam, which suggest that it’s Lauf’s own theory, birthed in 1981 when he was “contemplating the possible meaning of a 15th century Annunciation painting that hangs in The National Gallery.”

Next month: obsolescence!