A couple months ago, I decided that I wanted to begin learning a new language. I have been learning German for about 5 years at this point, and after years of classroom study and living abroad, I have reached a point where the amount of effort it requires to make even a small leap in practical knowledge is sometimes overwhelming.

I missed those earth-shattering “Aha!” moments that seem to happen all of the time in the early stages of learning a new language, so, I enrolled in a Japanese 101 class.

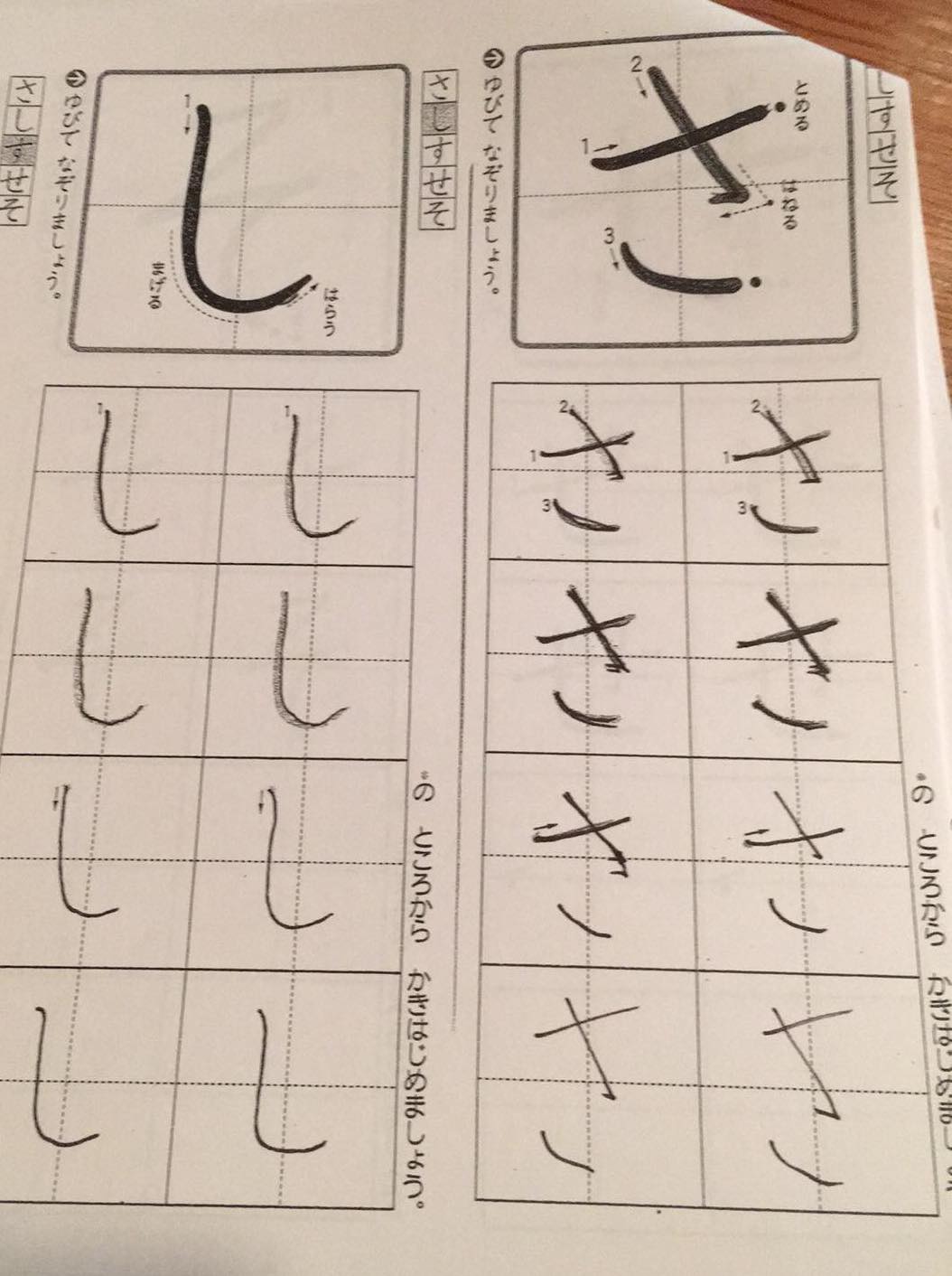

One of the things I was looking for in learning a new language was to learn a new writing system. Although I had to learn to read Fraktur script to do research in German, I still found myself wanting to get away from the Latin alphabet. I was excited to learn, then, that the standard pedagogical method of teaching Japanese as a foreign language is to start with the writing system; before being taught to speak even a single word or sentence, I was given several workbooks to use in practicing the writing system.

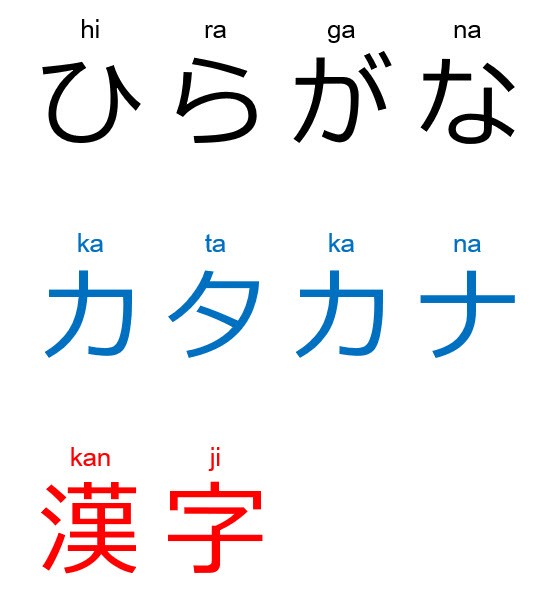

Modern Japanese’s writing system is interesting in that it contains 3 sub-systems within it: Hiragana (ひらがな), Katakana (カタカナ), and Kanji (漢字). Note the visual difference between the three systems. Hiragana characters are simple and feature lots of rounded and curved lines, Katakana characters are simple and look more jagged and square, and Kanji look very complex. (If Kanji characters look ‘Chinese’ to you, then you have good intuition; more on that later.)

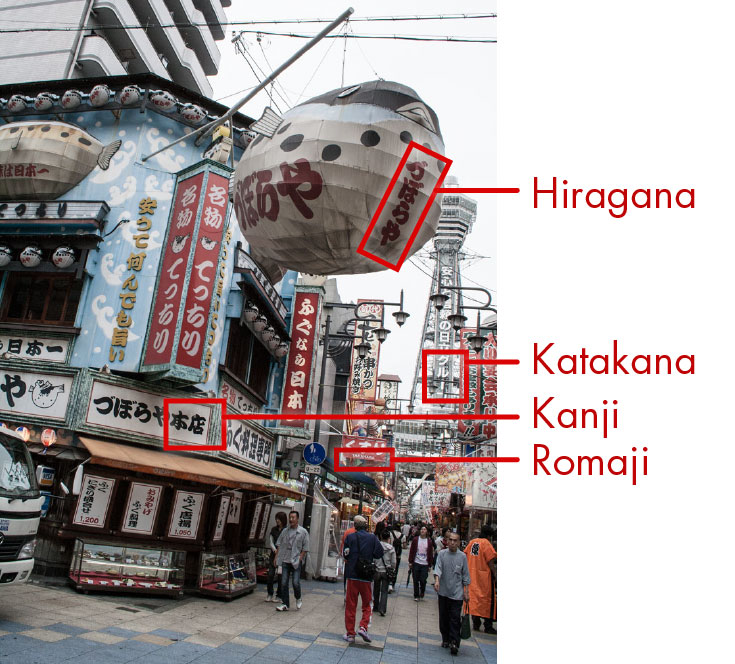

Although each sub-system has particular contexts in which it is preferred, modern Japanese is written using a mix of all three. If you look at the Japanese-language wikipedia page for Coffee, you’ll see all three writing sub-systems present in the first paragraph, seamlessly perched right next to one another in a single sentence. Although I’ve yet to visit Japan, I’m told that standing on a single street corner, it’s easy to find examples of all three (plus Romaji, Japanese written with the Latin alphabet).

Let’s begin by taking a closer look at Hiragana and Katakana, which are actually very similar systems, despite their contrasting appearances. They are similar in that both of these sub-systems are so-called syllabaries, systems of symbols which represent, that’s right, you guessed it, syllables. This system of writing contrasts with the Latin alphabet we use to write English, in which each symbol represents an individual sound. Before I get into what exactly a syllabary system looks like, let’s spend a moment talking about syllables.

When we talk about syllables, we are talking about the units of speech that we use to organize sounds into segments. In English, each syllable has at its core a vowel sound which is surrounded on either side by consonant sounds. For instance, in the word ‘dragon,’ we count two syllables: drah-guhn. If we imagine for a second that English used a syllabary for its written system, maybe we would write the word ‘dragon’ as follows: §£, where the § symbol represents drah and £ symbol represents guhn. Instead, with the Latin alphabet, we use these six letters ‘d-r-a-g-o-n’ to represent the following six sounds: /d/-/ɹ/-/æ/-/g/-/ə/-/n/.

As syllabaries, each Hiragana and Katakana character represents one syllable of the spoken language. For example, the word ‘cat’ in Japanese is pronounced ‘neko’ and is comprised of two syllables: ne-ko. The standard way of writing ‘cat’ in Japanese is using Hiragana, and the word looks like this: ねこ. (ね = ‘ne’ and こ = ‘ko.’) Each character represents one syllable and only one syllable. If you read the ね character, you know that it will always be pronounced as the ‘ne’ syllable, with no exceptions. Contrast this with the letter ‘a’ in English, which is pronounced differently in all of the following words: man, yacht, caught, alphabet. Compared to English, Japanese is a relatively simple language in terms of its phonology, meaning the inventory of sounds it contains. While American English speakers have as many as 15 distinct vowel sounds (depending on dialect), Japanese speakers have 5: /a/, /i/, /u/, /e/, /o/.

Katakana works in the same way. In fact, you could also write the word ‘cat’ using Katakana. Both of the two syllabic sub-systems contain 46 symbols, corresponding to the 46 commonly used syllables in the Japanese language. ‘Cat’ in Katakana would look like this: ネコ. You probably wouldn’t often see ‘cat’ written with Katakana, though, because of the two different contexts in which the different sub-systems are used. We’ll discuss these contexts for Hiragana and Katakana before moving on to the third sub-system.

As a general rule, Hiragana is used to write some common native Japanese words (like ‘cat’), grammatical markings on words (think ‘-ing’ suffix in English), and for function words and particles. It appears to be the work horse of the language, the basic words and the grammatical glue that binds them together. It’s not flashy, doesn’t put on airs; it does its job and then sits back down. Katakana, on the other hand, has a glossier feel to it. It’s often described as the equivalent of the English italics because of its ability to stand out visually. It’s typically used with foreign loan words, company names, scientific and medical names, and things that are meant to be emphasized. For English speakers, a good analogy that I’ve seen mentioned to help understand the feeling of Katakana is to think of all of the long Latin and Greek words which features ‘y’s, ’x’s, and ‘ph’s, letters that are not commonly found in simpler ‘english’ words (etymologically speaking). When we see a word like ‘hypophosphate,’ we are visually cued as to the origin of the word. Similar with Katakana and foreign loan words like ‘coffee’ (コーヒー) which are almost always written in Katakana.

But why two completely separate and redundant sets of symbols? The answer, as it always is when it comes to seemingly confusing or inefficient systems in language, is weird historical reasons. The specifics of why and how each sub-system developed are debated, but without going too deep into detail about something which I am not at all qualified to speculate upon, it is sufficient to know that each system developed separately (although from a common ancestor) and as some kind of simplification of the Chinese writing system, which was introduced to Japan sometime in the first few centuries AD, and is still used today as the third sub-system: Kanji.

Kanji, despite its complexity, is a very important part of the Japanese writing system. Looking at a paragraph of Japanese text, it is very easy to pick out which characters are Kanji, due to their relative complexity, even for someone who has zero experience learning Japanese. Whereas the Hiragana and Katakana systems are syllabaries, Kanji is a logographic sub-system, similar to ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, wherein each character represents a word or phrase. For instance, the following Kanji means “fabulous mythical bird; imperial”: 鸞. That’s a lot of meaning to pack into a single character on the page. (But hopefully you can also imagine the headache presented to those learning the language, as each Kanji must be individually learned and memorized, along with its pronunciation.) Although there is no definitive count of Kanji in Japanese (ditto for Chinese), there are about 50,000 Kanji recognized in Japan’s gold-standard dictionary. As someone hoping to learn the language, however, I take heart in the fact that only about two or three thousand (!) Kanji are regularly used.

Why have three sub-systems, though? Doesn’t this seem overly complicated? You wouldn’t be the first person to point this out. Despite being an entirely separate and unrelated language to Chinese, both phonologically and grammatically, Japanese’s writing system is very influenced by that of the Chinese, which has been at various times a sort of nationalistic sore-spot. As I mentioned before, even Hiragana and Katakana are based on simplified Chinese characters. There have been various calls over time to change the Japanese writing system to move away from its reliance on the complicated Kanji system, and although the system has been reformed and standardized over time, major efforts to completely move away from the Chinese system have proved unsuccessful, at least in Japan. In an successful attempt to improve literacy of the lower class, a 15th century Korean king created a syllabic writing system called Hangul, which replaced the Chinese writing system that was used up until that point.

As I stand here at the base of the language-learning mountain, gazing up at the thousands of arbitrary and complicated Kanji characters, I’ll keep my fingers crossed for similar changes to Japanese writing system, but it doesn’t seem likely.