This week, I’d like to talk a little bit about concrete, a material that I think has (unfairly) come to be associated primarily with Brutalism, and the divisive, often deeply annoying pro and anti-Brutalism constituencies (c.f., this old joke, accurate only when extended to both sides of the divide). The only thing I’ll really note on that point is that not all concrete architecture is an example of Brutalism; see, for example, Notre Dame du Raincy, a reinforced concrete church designed by Auguste and Gustave Perret, and one of my favorite buildings. (Almost every element of the exterior and interior is concrete, down to the grill work on the windows.)

Anyway, I was trying to figure out something about concrete formwork (we’ll get to it later) when I was instead taken in by this video. It shows a group of South Asian workers conducting a “slump test.” Upon first appearance, it’s a fairly enigmatic activity; they pour concrete into a cone, hack at it with a rod, then take the cone off and watch the mixture just sort of sink into the ground. What’s going on?

The slump test, as the name suggests, is a means of measuring how much concrete slumps (droops, sags, loses any spine it once possessed) in order to discern its consistency. You begin with what’s known as an Abrams cone—an open-ended mould that the concrete is poured into. Then, you use a tamping rod to pack the concrete into the cast, in much the same way that you might pack tobacco into your pipe, or weed into your bowl, with your index finger. (Non-smoking comparisons are eluding me here; I suppose it’s also something like packing sand into a bucket when making a sandcastle at the beach.) Then you take the cone off, and see how much the concrete slumps; the difference in distance between the top of the concrete pile and the top of the Abrams cone is the measurement of slump. As you’ve probably figured out, the concrete in the original video was poorly mixed; it collapses almost completely, perhaps because—as many insightful Youtube commenters suggest—there’s too much water in the mixture.

Generally, low-grade concrete won’t be used as a key structural support in a building, but it can be used in a variety of other ways: serving as a section of a building that needs to exist, but isn’t providing much support, or as temporary backfill that will be removed later on in the construction process. (For a much more thorough discussion on the pros and cons of using watered-down concrete, refer to this article from Concrete Construction.)

I’d like to move now from low-quality to high-quality concrete by exploring the use of concrete in the construction of Toyo Ito’s Meiso No Mori Municipal Funeral Hall in Kakamigahara, a city in Japan a few hours west of Tokyo.

In this case, the entire flowing roof canopy is made of concrete; contrast that with Zaha Hadid’s similarly sinuous Serpentine Sackler gallery, which is built of glass fiber. I want to explain part of the process of construction. (I’m leaning heavily on this Architizer article, which in turn relies heavily on Georg Windeck’s Construction Matters, which…I have not been able to find online for less than $25. If you have a pdf, hit me up!)

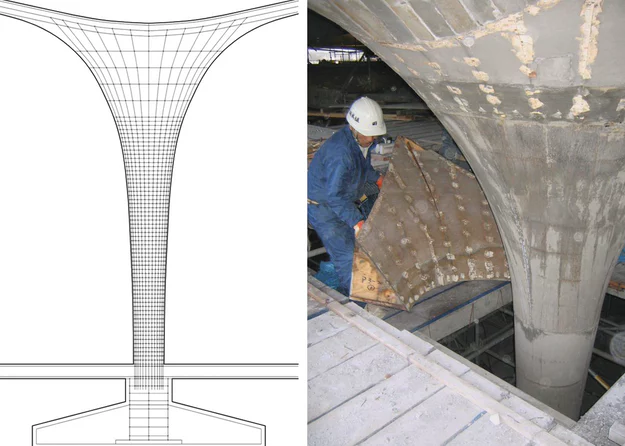

The most difficult aspect of the construction, essentially, was creating the plywood formwork—the mold that shapes the concrete. The formwork for each column supporting the roof had three portions, each one a gradually expanding ring. That’s what creates the gentle, funnel-shaped curve of the column below.

In order to ensure that the column itself will be strong enough to support the roof—since, as the upper part of the column expands, the weight that each part of the column can handle decreases—steel rings were inserted into the column, adding to the load the building is capable of handling.

The canopy itself had widely variable levels of stress across its surface. (This makes a lot of intuitive sense; think of how evenly stress will be distributed across a flat roof.) In order to ensure that the roof wouldn’t buckle, the architects had to insert steel mesh—small, latticed wires of steel, basically—as extra support. After construction, the white finish was applied, creating the vaguely ethereal feel of the final product.