Schools play an inordinately large role in the life of a child—especially in the United States, where schools are usually the center and lifeblood of juvenile social life, providing clubs, sports, and other after-school activities. Speaking from my experience, the schools I attended were such a central pillar of my young life, that it seemed impossible for me that other children built their lives around similar, yet slightly differing systems. It wasn’t until I got to college that I learned that many American children don’t attend a “junior high school” for grades 7–8, but instead are in “middle school” from grade 5 until grade 8. Even now, knowing that my experience with the organization of the school system in my home town is not the same experience as every other American, I still find it difficult to imagine anything else.

Imagine the mental shock I underwent—and am still undergoing—when I moved to a foreign country to work as an English teacher in a completely different school system. Although I’ve adapted to the model here in Austria enough to perform my professional duties, I still feel a sense of uneasy dizziness, like being thrown off balance after jumping off a spinning carousel, when I think: The children I’m teaching here have a completely school-world than the one I grew up with. That there are differences in educational systems between countries, between cultures, is obvious, of course. I didn’t come here expecting it to be the same. But there’s a big difference between knowing something theoretically and seeing it and living with it first-hand.

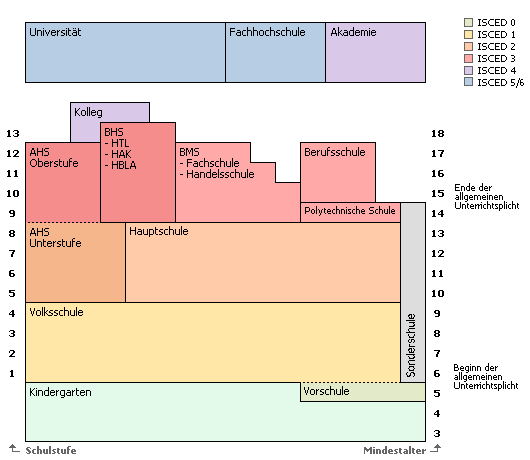

Starting at the beginning of a child’s education experience, things look similar enough to the American system: Optional pre-school from ages 3–4 and Kindergarten (German word, by the way: lit. Children Garden) from age 5–6. Ages 6–10 are spent at a Volksschule (elementary school) in grades 1–4. After this, however, things look a lot different. Whereas in the American system, all children go to the same school, but might be “tracked” into different levels (advanced, intermediate, basic, etc.), the Austrian system begins separating children at the age of 10 into completely different schools. These schools are almost always in different buildings, sometimes in different towns.

Students who seemed destined for university are sent at the age of 10 to a sort of “pre-high school,” sometimes found in the same building as a high school. Less achieving students are recommended to attend a less-rigorous “middle school.” At the age of 14, students are then recommended to any number of different high schools or high school alternatives—the variety of which is so large and complex, it requires a pretty serious chart to explain. The basic idea though, is that some students are sent to a “grammar school” which prepares them for university educations in either the humanities or sciences, while other students are send to technical or business training schools, which allow them to begin working skilled, well-paid, sometimes highly-technical jobs right after finishing high school.

My thoughts on the benefits and malefits of this model would take a few more blog posts, but please email me if you would like to discuss! The bottom line is: the system here is different, and it still feels weird to my Ohio-born and -bred mind that school—such an unshakable foundation of childhood—can even look different.