The other day I walked out of my room to find a miniature ruckus happening upon the wall just outside of my door. I first heard a buzzing noise and looked around to find a small fly trapped in a spider’s web. I paused to watch the fly in its struggle, and eventually a small, grey-brown spider trickled down its web to meet its catch of the hour. Across from this spider web was yet another different-looking spider, waiting patiently for a fly as well. And then just further down, a third even larger spider web hung from the corner below the ceiling. Each web with a number of flies preserved in the corner for later consumption.

Right outside my door, a small ecological competition occurred every day. The flies in the hallway traversed the gauntlet of webs just to eat the PB&J sandwiches in my room, and the spiders sat poised outside my door to collect their catches of the day. On a small-scale, the spiders in the hallway represent what ecologists have theorized to be a fundamental source of biodiversity in larger communities of organisms.

A study was published in Nature (Grilli et al.) about five days ago with a new understanding of how competition between species creates stable, yet diverse, ecological communities. Their model suggests that when species coexist, they operate within a modified version of “rock-paper-scissors”: each species has its move that can trump the move of another species, while also susceptible to lose (or die) via the move of a third species.

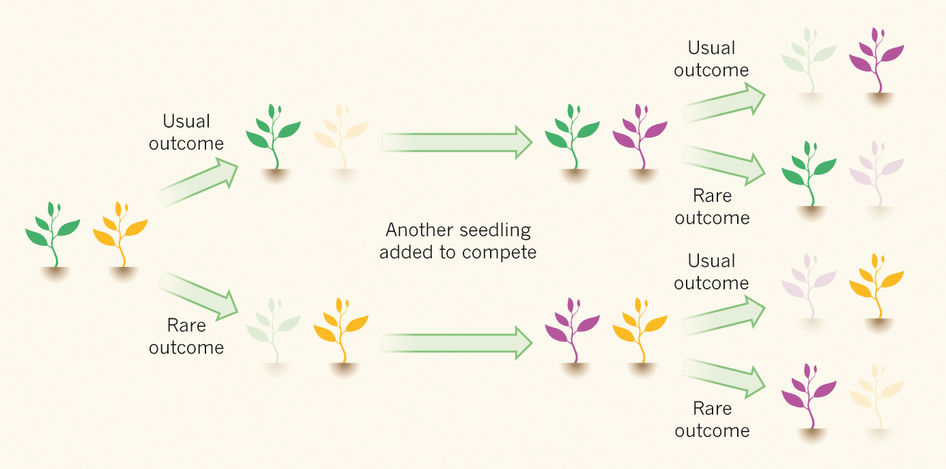

Thus, within the ruckus I stumbled upon, we first have two spiders: Spider Rock and Spider Scissors. Spider Rock caught the fly outside my door. And Spider Scissors across from her did not. Let’s say this is the usual outcome and Spider Rock usually catches more flies than Spider Scissors. Left alone, the two spiders maintain a hierarchy of one spider outcompeting the other. Rock beats Scissors. But say, a new spider comes in, Spider Paper, right down the hall, and he recently just built a pretty large and exceptionally sticky web. And Spider Paper is reporting higher numbers of flies caught than Spider Rock. Paper beats Rock. The hierarchy has been equalized! Spider Scissors won’t necessarily die out because of reduced number of flies in Spider Rock’s web, giving Scissors a new chance to catch more. And, Scissors can beat Paper now, theoretically.

There’s just one twist though.

In their modeling scenario, the researchers Grili et al., report that in the real-world, there are always rare outcomes. That is, if I played rock-paper-scissors with you, maybe 1 time out of 10 my scissors beats your rock. The study suggests that, in nature, when this rare outcome occurs (due to disease, mutation, etc.), it works to create more stability within a community where many different species are coexisting.

One day, Spider Scissors beats Spider Rock. Spider Rock dies and doesn’t reproduce. Spider Scissors has more food and multiplies his spider army to take on Spider Paper. And the cycle goes on and on.

I hope my summary wasn’t too confusing. And if you’re not convinced or need more info, the article can be found here :)