One of the courses I’ve been taking this quarter has me working pretty closely with some of Franz Kafka’s lesser-known stories, sketches, aphorisms, and diary entries. As a result, I’ve been spending a lot of time in the PT2621.A26 section of our library, where all of the books written by Kafka, written about Kafka, or written about about books written about Kafka (Academia can be confusing, sometimes) are stored. While poking around for some material about a story I was reading which is sometimes called „Der Jäger Gracchus“ (The Hunter Gracchus), I discovered that not-only was the story never published during Kafka’s Lifetime, like most of his work, but that it was never even finished or edited by Kafka himself—it was simply pulled from some of the notebooks discovered in his desk after his death by his friend and editor Max Brod. These notebooks are now part of a collection called the Franz Kafka Ausgabe (FKA) and our library has a complete collection of their facsimiles, published by Stroemfeld Verlag.

Contained within these notebooks are pages of fragments of stories, sketches, notes, and even Hebrew exercises. After moving-in with his sister Ottla, Kafka notably changed the notebooks he wrote in from a Quart size to an Oct size, something which has been written about my more than a few Kafka Scholars, some of them attributing changes in Kafka’s style to the reduced size of each line in the newer, smaller notebooks.

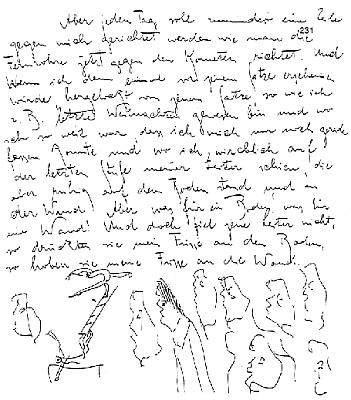

Looking at the original manuscripts, one also realizes how much of the material of each story was actually struck-through by Kafka’s own pencil. Kafka thought of the writing process as an extremely painful one, and this becomes apparent when one looks at the vicious crossing-outs, erasures, and large „X“s throughout the notebooks. This presents problems for publishers trying to decide what material to include in editions of Kafka’s stories: Should they include material that he crossed out, because of its value to Scholars and Fans, or should they respect his editing marks?

This is even more complicated when one considers that during Kafka’s lifetime, only a few collections of his short-stories were published. The three novels that he’s most famous for,The Castle,The Process, and Amerika, as well as most of his short-stories were published posthumously by Max Brod against the instructions from Kafka’s Last Will and Testament. Kafka instructed his friend Max to actually burn all of his manuscripts, notebooks, and letters, which, luckily for us, Max decided not to do. Some estimate that, despite this, about 90% of Kafka’s total work was burned by him while he was still living.

Even with the relatively small amount of material that still exists of Kafka’s, he is counted among the literary greats of the 20th century, especially in the German-speaking world, and looking at his original writing, in his barely-decipherable handwriting, and seeing the marks and drawings he makes on the margins is certainly something special.