The title of one of the courses I’m taking this quarter is „Biocentrism: The Concept of Life in German Art and Literature Around 1900.“ Throughout the course, we are looking at literature, art, film, and architecture, particularly in the German tradition, to explore the underlying thoughts and ideas which inform Biocentrism.

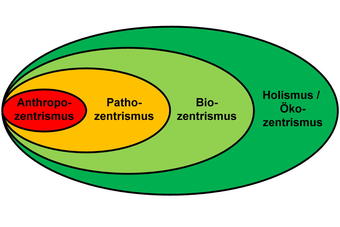

Biocentrism is an ethical system (you could call it a ‘world-view’) in which a ethical worth is assigned to all living things inherently. In contrast to other ethical systems, such as Anthropocentrism in which an ethical worth is only assigned to humans, Biocentrism widens the inclusion, assigning animals and even plants an inherent value based on their being alive. The concept itself is fairly academic, dealing more with questions like „what is a soul?“ and „how do we define life?“ than „should we eat animals?“ and „may I squish a spider?“, although the jump to questions of the latter sort is not a far one.

While Biocentrism provides an ethical worth to a broader set of organisms than more-limiting systems like Anthropocentrism, it still operates at the level of the individual organism: value is given to each human, every squirrel, and all trees. Broader systems like Holism or Ecocentrism avoid individuals and provide worth to entire ecosystems and biospheres, allowing the worth to trickle-down to its constituent members only by the virtue of their inclusion and participation in the larger system.

The political facets of Biocentrism have emerged out of a desire by some ethicists, Albert Schweizer being chief among them, to reconnect ethics to nature, and to provide for less human-centric views of the world we live in. According to him, the most fundamental fact of human consciousness is the realization that „I am life which wills to live, in the midst of life which wills to live.“

Just some food for thought.