In a class I’m taking on sensation and perception in the human brain, we recently read a research journal article inquiring about how our visual cortex is able to mark the “front” of an object. The “front” of an object must be clarified because in the actual world—set apart from our individual perceptions of the environment—the surface of an object does not have an objective label for its “front.” Instead, we designate this label to objects according to information we receive, such as an object’s direction of motion. But when this information is absent or weak, or has surfaces that have competing cues for being its “front”, we can then flexibly assign the “front” to an object (e.g. which side is the front of a motionless skateboard?). The experimenters, Yangqing Xu and Steven Franconeri from Northwestern University (hssss), test these ideas with a modified Necker cube (Demonstration: http://www.yorku.ca/eye/necker.htm) where two different representations of its possible “fronts” are given for participants to perceive. The participants are required to either change their perception when prompted, or change their perception spontaneously and signal when they view a new perception of the cube.

Click to read on…

This week, I got to handle and observe some actual human brains as a part of a Neuroscience class that a friend of mine is taking! She invited me to slip-into the class, which was having a „Brain Demo,“ given by Professors John and Stephanie Cacioppo. We made sure to get seats in the front of the class in order to have a front-row view of the demonstration, but to my surprise, we were all given rubber gloves and encouraged to walk about the classroom and view the multiple different brains they had on display.

Click to read on…

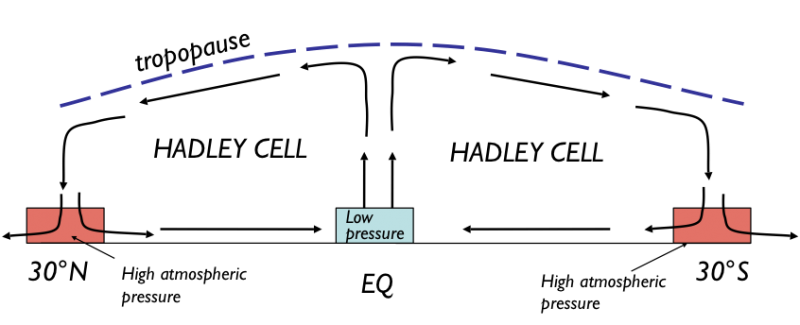

Due to the Earth’s curvature and its 23.5° axial tilt, the Sun’s energy only strikes the Earth’s surface head-on at a specific point, called the subsolar point. At this location, the sun is directly overhead and the very intense rays of sunlight hit the Earth exactly perpendicular to its surface, resulting in an atmospheric effect known as the Hadley Cell (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hadley_cell).

Click to read on…

When many people encounter the term „Animal Rights“ (sometimes followed by the word activist), they think of long-haired Hippie-Types chaining themselves to trees or bison, burning down factory-farms, and throwing red paint („lamb’s blood“) on people wearing fur coats. In my Animal Studies course, I encountered a few philosophers and ethicists writing on the subject of „Animal Rights“ (although not all agree with the use of this term) and discovered that even among pro-vegetarian thinkers, there exist many different theoretical and practical positions on how non-human animals should be considered and treated by humans.

Click to read on…

What’s at stake when people make music? Well…a lot of things. We opened up with this question on the first day of a class on “world-music”. The underlying field: Ethnomusicology, the study of people making music. Other questions that were brought up:

Click to read on…

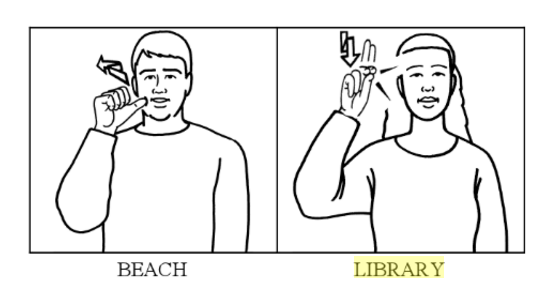

In Australian Sign Language (otherwise known as Auslan), the sign for LIBRARY is signed by moving the dominant hand next to the head and opening and closing the middle and index fingers into the thumb, a motion similar in form to the opening and closing of a hair clip. Like all languages, even spoken ones, signs in signed languages do not need to be iconic or representative of their significants; but the story of how this sign came to be also serves as a great example of how languages change and form.

Click to read on…